Bio

Reporter for ProPublica. I'm often tracking politics, rooting for the Cubs & the Cats, and listening to Curtis or the Clash.[Danielle Scruggs, special to ProPublica]

This article was first published in ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

The bank’s board meeting on April 28, 2016, started with a prayer. Then it turned to plans for keeping the bank alive.

That week, federal regulators had signed off on a deal allowing new owners to take control of Illinois Service Federal Savings and Loan, one of the last Black-owned banks in the country. For more than a year, regulators had warned the bank could be shut down if it didn’t raise capital. They had also ordered it to improve its management.

What’s gone wrong at Chicago’s last Black-owned bank?

This story was originally published by ProPublica Illinois

Combative and, at times, dismissive, Chicago’s first-term mayor gathers power as she leads the city’s fight against the coronavirus.

No one questioned that Mayor Lori Lightfoot has been firmly in charge of Chicago’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But during a briefing Lightfoot had with the city’s aldermen on March 30, she made it clear anyway.

Leaked Recordings Reveal Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot Firmly in Charge and City Alderman Left Largely on the Sidelines

ProPublica Illinois reporter Mick Dumke looks at the state’s political issues and personalities in this occasional column.

The Chicago City Council’s Transportation Committee has an annual budget of more than $467,000 to cover expenses related to its work on legislation and government oversight.

But little of that work was on display during the committee’s March 6 meeting.

“Fairly quick agenda this morning,” the committee chair, Ald. Anthony Beale, said at the start. He and the six other aldermen then ran through its 70-page agenda in about 23 minutes, approving dozens of ordinances that dealt with hyperlocal administrative matters such as signs, awnings, light fixtures or sidewalk cafes for particular addresses.

That was typical for Beale’s committee. While it rarely does in-depth legislative work, the committee and its budget have been far more valuable for Beale as perks.

Beale, alderman of the far South Side 9th Ward, has used committee funds to hire employees — eight were on the payroll as of December — though he acknowledged they don’t spend all their time on committee work. He’s spent Transportation Committee money on his own transportation, including payments on a Chevy Tahoe SUV and thousands of dollars in parking expenses. And committee funds have gone toward furniture for his City Hall office, including a bourbon cherry wardrobe cabinet, according to records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

The Transportation Committee isn’t an outlier.

At great cost to taxpayers, the City Council’s 16 legislative committees are the heart of a favor-trading system that’s enabled mayors to rule like monarchs distributing favors to loyalists. At the same time, the committees have failed to provide even basic oversight of city government.

Many meet infrequently, and when they do, they frequently rubber-stamp agendas in a matter of minutes — often without a quorum of half the members. The budgets for the committees added up to $5.8 million in 2018, but the amount each committee receives is not tied to the volume of legislation it reviews or the regularity of its meetings.

Instead, funding appears more closely aligned with tradition and the clout of the chairs.

Chicago aldermen have also made it almost impossible for the public to see what they’re up to. Committee meeting schedules are posted online and meetings are open to the public, but they’re not broadcast, recorded or transcribed — unless a chair makes arrangements.

The topper: The council has passed laws to make sure committee operations are kept from any oversight. In 2016, aldermen voted 25-23 to kill a proposal to allow the city’s inspector general to investigate and audit the council. Aldermen then passed a substitute ordinance that explicitly blocked the inspector general from looking into many council functions, including committee spending.

Mayor-elect Lori Lightfoot, who will be sworn in with aldermen on Monday, has called for changing the law so the inspector general can audit the council and its committees. She and key aldermen continue to negotiate over who will lead the committees. As current chairs maneuver to hold onto power, reformers say it’s time for significant changes.

City Inspector General Joe Ferguson said Lightfoot and the new council face an urgent need to open the books and bring accountability “with respect to budgets, expenditures, staffing and operations at both the whole Council and Committee levels.”

“Government cannot fully escape corruption, mismanagement and waste without accountability,” Ferguson wrote in a statement responding to ProPublica Illinois’ findings. “That applies as equally to a legislative body as it does an executive, and even more so in Chicago, with its history of a weak, compliant City Council most noted for a decades-long trail of corruption. At this moment in the City’s history, both the public and the incoming Mayor desperately need a productively engaged City Council that fully inhabits its legislative oversight responsibility.”

In most legislative bodies, members pick their own leaders and committee chairs. The Chicago City Council’s rules say that’s what aldermen should do as well. For decades, though, the mayor has picked council committee chairs. It’s no secret at City Hall that only aldermen who support the mayor’s initiatives are rewarded with the posts, though they often claim otherwise.

As Ald. Walter Burnett Jr. tells it, he was shocked when, in 2007, former Mayor Richard M. Daley offered to make him chair of the Special Events Committee. Burnett had never led a committee before. And he had been pushing an affordable housing plan that was more aggressive than the mayor wanted.

“I thought there might be a hit out on me,” Burnett joked. Instead, Daley came up with a watered-down affordable housing plan. After Burnett signed on, “the next thing I knew, I got a committee.”

Despite their back-and-forth over affordable housing, Burnett had supported almost all of Daley’s agenda, including the mayor’s plan to demolish dozens of public-housing buildings and replace them with mixed-income developments.

In 2011, Rahm Emanuel campaigned for mayor on a promise to rid City Hall of corruption. He even suggested he might replace Ed Burke, the dean of the City Council, as chair of the Finance Committee, the council’s most powerful. Once in office, Emanuel eliminated three other council committees and shaved funding for others.

But soon after, the city’s annual budgets — proposed by the mayor and approved by aldermen — began boosting the money available to committees again. By 2017, the council committees were spending more than when Emanuel became mayor.

Emanuel also let council insiders stay on as committee chairs — including, most notably, Burke — so he could count on their help advancing his agenda. Some loyalists got promotions. In 2013, for example, Emanuel shifted Burnett to the Traffic Committee, which had an annual budget of about $215,000, a bump from the $155,000 he had to spend as Special Events Committee chair. The Traffic Committee budget has since grown to about $249,000.

Emanuel’s chosen committee chairs have proven to be reliable supporters. Two of the current chairs sided with the mayor on 93% of divided council roll call votes from 2017 to 2018 — and those are the most independent voting records of any of the committee leaders. Burnett and five others voted with Emanuel 100% of the time, according to a study by political scientists at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The committees are valuable because of a simple fact: Like most public officials, every alderman would like more staff and money to work with.

For years, the city’s annual budget — approximately $10.7 billion for 2019 — has allocated funds for each alderman to hire three aides. Most aldermen say that’s not enough to manage their daily barrage of constituent service requests, let alone to prepare for their jobs as legislators.

Aldermen have a limited number of options for adding staff. They can try to cut office expenses and spend more money on employees. They can also use campaign funds to hire more people, the approach taken by Brendan Reilly of the downtown 42nd Ward.

That’s not easy for most aldermen, especially those who struggle to raise money.

Chairing a committee offers another possibility. Committee staff members are exempt from city rules meant to prevent political hiring and firing, which means the chairs can fill the jobs any way they want, for any reason.

Tom Tunney, the current chair of the Special Events Committee, said he needs extra help to keep up with constituent needs in his busy ward, the 44th, based on the North Side’s Lakeview neighborhood.

He acknowledged that most of the legislation his committee oversees — concerning festivals, cultural events and other matters connected to the arts — comes from the mayor’s office and the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events. The committee had three employees as of December, but since they only spend about a week each month preparing for committee meetings, Tunney also assigns them to help with issues in his ward.

“Do they just work on committee stuff? No,” Tunney said.

Tunney conceded it’s not fair that committee chairs essentially get more help to take care of their wards. But he’s also skeptical of proposals that would require committee employees to limit their work to committee matters, because he doesn’t think they would have enough to do.

“I wouldn’t agree with that because practically; I want my people working all the time, given my workaholic nature,” he said.

Last month, Tunney said he would like to be considered for Finance Committee chair after the new council is sworn in on Monday, and other committee chairs are lining up behind him.

Burnett said he, too, counts on committee staff to help with ward matters. At the end of 2018, he had eight employees on the Traffic Committee payroll.

“It helps you with your ward, especially if you’ve got a ward like mine,” said Burnett, whose 27th Ward includes parts of the near North and West sides that have boomed with development over the last two decades. “I get everything from yuppies worried about permit parking to people [dealing with] sewage. It’s never ending. … So the extra staff people help, and they do dual roles. Everybody works on the ward and everybody works on the committee, too.”

Burnett said his committee employees put in a lot of work to prepare for the committee’s meetings. But that wasn’t evident when it convened on March 6.

Several minutes after the meeting was scheduled to start, the chairman’s seat was still empty. So were most of the seats around them. Only four of the committee’s 16 members had shown up.

Finally, an aide to Burnett got a call on his cellphone and waved Marty Quinn over. Quinn, alderman of the 13th Ward on the Southwest Side, appeared taken aback for a moment. Then he understood: Burnett wasn’t going to show. Quinn was going to have to lead the meeting.

Under City Council rules, at least half of the members of a committee need to be present for a quorum. But neither Quinn nor the other three aldermen noted that they were four short. Quinn gaveled the meeting to order and moved to pass the first 19 proposed ordinances on the committee’s 12-page agenda.

“All those in favor?”

“Aye!” the other three aldermen said in unison.

“In the opinion of the chair, the ayes have it,” Quinn said.

As is usually the case with the Traffic Committee, each of those ordinances concerned parking restrictions, loading zones or traffic signs for single addresses or streets. And if the local alderman has approved, the committee signs off.

In a series of rapid-fire motions and choruses of “aye,” Quinn and his three colleagues ran through the next 10 pages of ordinances with no discussion or break in their rhythm.

All told, the meeting took less than three and a half minutes.

The public has no ready way to see how many people are hired by the committees or what they do. Annual city budgets allocate money for committee staff. But only the budget for the Finance Committee specifies the number or titles of committee employees, giving the other committee chairs the power to use those funds as they see fit.

At the end of 2018, council committees had a total of 133 employees, according to city payroll records. That’s 108 more than were listed in the city budget approved by aldermen and released to the public. Most of the employees are listed in payroll records as “legislative aide.”

The Finance Committee has long had the largest committee budget, as well as the broadest jurisdiction, including city bonds, taxes, legal settlements and privatization deals. It also housed the city’s workers’ compensation program. In January, Burke, its longtime chairman, was charged in federal court with attempted extortion; Burke has denied any wrongdoing. Emanuel then had Burke deposed as finance chair and moved the workers’ comp program to the city comptroller’s office.

For years, the Finance Committee’s accounting was even more opaque than other committees’. According to the city budget, the Finance Committee had a 2018 budget of $2.3 million, which included the salaries of 25 employees. But expense records show that Burke had access to far more money and workers. Burke kept between 61 and 78 people on the payroll at different points in the year, costing a total of about $3.4 million in worker pay. Employees listed as full time were paid salaries ranging from about $21,000 a year for a legislative aide to $171,000 for the chief administrative officer of the workers’ comp program.

Following the Finance Committee money gets tricky fast. In addition to money allocated for the committee, Burke also paid workers out of funds he controlled in other city departments. One employee was paid out of the budget for the Fire Department’s workers’ compensation costs; others were covered out of allocations for “investigation costs” buried deep within the budget.

At least four employees were paid from multiple funds during the course of the year.

Last December, the Finance Committee transferred $862,000 from its reported expenditures to the balance sheets of other city departments. The end-of-the-year accounting maneuver came after Burke’s staff said some employees assigned to the committee should have been paid out of funds available for the workers’ compensation program. The spending records don’t show what the employees’ duties were.

The complicated money flow — and lack of oversight — put Burke in the enviable position of being able to dispense favors and largesse to other aldermen. For years, he essentially loaned employees to other aldermen who needed help, as WTTW reported in March. On occasion, the Finance Committee paid expenses for other aldermen, such as when it reimbursed 40th Ward Alderman Pat O’Connor about $2,900 total for travel to conferences of the National League of Cities in Nashville in 2015 and Kansas City the next year. O’Connor did not respond to a request for comment.

From 2015 to 2018, the Finance Committee also paid more than $46,000 to cellphone provider Verizon Wireless. Invoices don’t provide details about the account or why the bills were so high.

Burke didn’t respond to requests for comment.

As chair of the Committee on Committees, Rules and Ethics, 8th Ward Alderman Michelle Harris oversees council procedures and has the power to decide which legislation is assigned to which committees, or to hold up legislation altogether.

“I do everything I can to be aboveboard and be transparent because I am the rules chair, but every now and then it doesn’t work out that way,” Harris said in an interview.

In April 2018, $8,820 in committee funds went to pay a South Side company to print and mail an 8th Ward newsletter, according to a copy of the invoice obtained from the city under the Freedom of Information Act.

Harris said the mailing was focused on city services and wasn’t political, but she conceded it should have come out of her ward account. She blamed the error on a new employee and promised to “have her re-trained.” Harris also wondered why city finance officials didn’t catch the mistake.

“What I’m further concerned about is that it wasn’t flagged anywhere along the process,” she said.

Between 2015 and 2018, Harris paid $82,000 in Rules Committee funds to The Salient Group, a downtown firm, for what was described in a February 2018 invoice as “PR Consulting.”

Harris said Salient’s president has attended committee meetings and helped Harris respond to news coverage about her role as chair, such as criticism that she has buried legislation when it was opposed by Emanuel and his allies.

“I’ve gotten torn up on by some people, so I’ve had to come up with a strategy about how to deal with those issues,” Harris said. Asked if all of the PR work was connected to the committee, she said, “You are 10,000% correct.”

Loading...

Beale, chair of the Transportation Committee, also dipped into committee funds for public relations.

Beale became the committee’s leader after a slow, steady climb up the City Hall ladder. In 2007, Daley picked Beale to lead the council’s Landmarks Committee. Its previous chair, Arenda Troutman, had been charged in federal court with taking a bribe and then lost her reelection bid.

Three years later, Daley moved Beale to the helm of the Police and Fire Committee, which had a larger budget. When Emanuel was elected mayor in 2011, he shifted Beale to chair the Transportation Committee.

The new post was another boost for Beale. The Transportation Committee has an annual budget more than twice as large as his old committee’s. And most of its work consists of rubber-stamping hyperlocal administrative ordinances. Between 2015 and 2018, 99% of the ordinances introduced to the committee were passed, records show, typically without discussion or debate.

In addition to putting eight employees on the payroll, Beale used committee funds to pay $15,000 in 2015 and 2016 to the public relations firm MK Communications for “professional services,” including “project strategy, planning and management, media, writing and editing,” according to invoices.

Another $13,000 went to Rightsize Facility, an office furniture company, for items that included a bourbon cherry wardrobe cabinet delivered to City Hall, records show.

Beale also used committee funds to pay for a car and parking costs. More than $9,000 went to GM Financial Leasing for a 2015 Chevy Tahoe SUV, records show. Another $11,000 covered parking expenses.

Pointing to the committee’s 70-page agenda after its March meeting, Beale said all his committee staff positions are needed.

“That’s a lot of work, man,” he said.

But Beale said those employees don’t limit their work to committee matters.

“I mean, people call downtown for a city service, of course they’re going to serve the people,” Beale said. “I’m not going to tell a [committee] staff person, ‘This is an aldermanic call, someone calling to have a street light put on,’ and transfer that call. You take care of that city service. You’re still doing a service to the public.”

Marilyn Katz, the president of MK Communications, said her firm works on a range of issues with Beale. They include matters before the committee, such as taxi regulations, as well as ward issues such as housing and the opening of a Whole Foods store. She said she couldn’t comment on the committee expenditures but would ask Beale.

The alderman didn’t respond to that or other requests for comment about committee spending.

In recent weeks, Beale has been among the council chairs lining up support from colleagues to hold onto their committee posts. They’ve also been working to block 32nd Ward Alderman Scott Waguespack, a Lightfoot ally and head of the council’s Progressive Caucus, from becoming the next chair of the Finance Committee.

Perhaps the highest cost of the current committee system is the hardest to measure: the failure of the City Council to provide oversight of city government and, when necessary, serve as a check on mayoral power.

More than a dozen people were reportedly shot over the first weekend of April — a number that’s not unusual in Chicago as the weather warms up. But the city’s ongoing struggles with gun violence were not mentioned during the April 8 meeting of the Committee on Public Safety. Just one item was on the agenda: an ordinance that would temporarily allow helicopters to land near McCormick Place so they could be exhibited during the upcoming convention of the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

The committee rarely holds discussions of crime trends or policing strategies. That’s been true even within the last year, as aldermen have drafted and introduced proposals to create community oversight of the police department. After one proposal sat in the committee for two years, aldermen shot it down last fall. The committee chair, Alderman Ariel Reboyras, of the 30th Ward, hasn’t held votes on other proposals.

Last October, 20 aldermen signed a letter asking Reboyras for a hearing on a report from the office of the city inspector general that found police officers assigned to city schools lacked proper training, standards and accountability. Reboyras hasn’t called that hearing either.

From 2015 through 2018, 12 of the 25 ordinances approved by the committee concerned donations of used fire trucks and other vehicles to nonprofit groups or towns in Mexico, Puerto Rico or Argentina. The committee also considered 25 mayoral appointments to city boards. It approved all but one.

Only six of the committee’s 19 aldermen were present for its April 8 meeting, well below the 10 needed for a quorum. Once again, no aldermen asked for a quorum vote, so the meeting continued.

The committee members had just two questions about the helicopter-landing proposal. Had it been done before? Yes, a police sergeant told them — in 2011 and 2015, when the police chiefs last held their conference in Chicago.

Reboyras, the chair, asked the other question: “Where was the previous conference held?”

Orlando, the sergeant told him.

With that, the committee voted unanimously to approve the ordinance. The meeting lasted about five and a half minutes.

As of the end of last year, the committee had two employees, records show. But Reboyras didn’t want to talk after the April meeting about their responsibilities.

Asked if they spend all their time on committee work, he said, “What are you trying to get at?” Asked again if the committee staff do work in his ward, Reboyras said, “Yes, they do,” and walked off.

At Chicago’s City Council, committees are used to reward political favors and fund patronage

ProPublica Illinois reporter Mick Dumke looks at the state’s political issues and personalities in this occasional column.

Lori Lightfoot was running early. Most political campaigns struggle to stay on schedule, especially as Election Day speeds closer. But in the final stretch of the runoff election for Chicago mayor, Lightfoot appeared to be rolling with such confidence that her campaign started holding rallies well ahead of their announced start times.

Meanwhile, Toni Preckwinkle, fighting the perception that Lightfoot had all the momentum, showed flashes of the candor and personality many voters wish they had seen from her throughout the mayoral race.

“This has been an —” Preckwinkle paused during our interview last week before finishing the sentence: “interesting campaign.”

Chicagoans don’t have much experience with open mayoral elections — this is the first in decades that doesn’t include an incumbent or anointed heir. But it turns out that all sorts of things can happen when democracy moves in. After Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced in September that he wouldn’t seek a third term, 14 candidates made the ballot to succeed him.

Because none received a majority in the first round of voting in February, the top two finishers — Lightfoot and Preckwinkle — went into the April 2 runoff.

Whoever wins will become Chicago’s first black woman mayor.

On many issues, they share nearly identical positions. Both Lightfoot, an attorney and first-time candidate, and Preckwinkle, the Cook County Board president, present themselves as progressives who will focus on safety, schools and jobs in the city’s neighborhoods. Both say they'll address the needs of South and West side communities desperate for investment as well as rapidly gentrifying areas extending from downtown where housing costs are soaring.

But voters are demanding a change after eight years under Emanuel and 22 years under his predecessor, Richard M. Daley. In response, the two candidates have tried to cast each other as part of the city’s political machine. Lightfoot has hit Preckwinkle for chairing the Cook County Democratic Party and receiving fundraising help from Ald. Ed Burke (14), who was charged in federal court in January with attempted extortion of a Burger King franchisee in his ward. For

her part, Preckwinkle calls Lightfoot “the ultimate insider” for accepting appointments in the Daley and Emanuel administrations.

To get an up-close glimpse of how the race was unfolding, I asked both campaigns if I could hang out with them for a bit. Aides to Lightfoot invited me to follow her to several get-out-the-vote stops, while Preckwinkle's team scheduled me for an interview at her campaign headquarters.

When Lightfoot arrived early for a rally at her campaign field office on West 47th Street, in the working class Brighton Park neighborhood, her volunteers and supporters were ready. As Lightfoot strode into the storefront office in a flash of green — wearing the emerald coat and green-checked fedora she’d put on for the St. Patrick’s Day parade earlier that day — dozens of her backers chanted “LO-RI! LO-RI! LO-RI!”

“We have the opportunity to do something really special,” Lightfoot told the group crowded around her, most of them Latinx younger than 30, as an aide translated her remarks into Spanish. “It’s really clear that black and brown communities are not getting their fair share of resources.”

Lightfoot then led the room in a chant of “Sí Se Puede,” or “Yes, it can be done,” a longtime activist and civil rights rallying cry.

Lightfoot’s critics on the left say her record is anything but progressive. A former federal prosecutor, Lightfoot was appointed by Daley to lead the Office of Professional Standards, which oversaw police accountability from within the department, and then was picked by Emanuel to preside over the police board, which reviews police discipline cases. She repeatedly failed to hold officers accountable for misconduct, her critics charge, with some going so far as to say she’s essentially a cop herself. Lightfoot counters that she worked to change the system from within.

“We can’t just yield the floor to people whose views we don’t agree with,” she said in a recent interview. “We’ve got to be in the room, because if we’re not, our people are always going to get screwed.”

None of that came up when Lightfoot greeted potential voters on the 1600 block of West 47th Street in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. As Lightfoot bought tamales from a street vendor, a beaming young mother nearby turned to her curious daughter and said, “It’s Lori Lightfoot — in our neighborhood!”

Lightfoot stepped into a supermercado, where shoppers and employees stopped what they were doing while she introduced herself and shook hands. A cashier explained who Lightfoot was to her customers.

“She’s going to be the next mayor of Chicago,” the cashier said. She laughed, then added, “Well, she might be.”

Right. This being an actual election, the voters have to weigh in first, and Preckwinkle vows it’s not over.

During much of the mayoral race, Preckwinkle has seemed defensive, evasive and scripted, even reading talking points from her notes during candidate forums. But when I sat down with her last week at her River North campaign headquarters, Preckwinkle resembled the blunt, confident politician I’d interviewed in the past — including her first two terms as county board president, when she focused on repairing county finances and addressing racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

I suggested she had been playing defense since the revelations about Burke and his fundraising effort for her, and the campaign had not gone as she’d expected.

“That is an understatement,” she said, and then laughed.

Preckwinkle noted, as she has before, that when she served as an alderman from 1991 to 2010, she had an independent record. She was not friends or allies with Burke, who helped advance Daley’s agenda while Preckwinkle often opposed it.

But it’s not clear if that part of the story ever sunk in with voters.

“I don’t know,” she said, though “it’s what I always say.”

Voters have other concerns, Preckwinkle said. “When I go out in the communities, what people are really talking about are their neighborhoods. In Logan Square, Humboldt Park and Pilsen, I hear people say, ‘We’ve lived in this community for generations, and I’m not sure we can afford to stay here.’ On the West Side, all you hear is, ‘There’s never any investment in our communities.’ Both of those challenges have to be addressed.”

When I asked how the city would find the resources to rebuild areas in need, she — like Lightfoot — didn’t have specific answers. But Preckwinkle said her record as alderman and county board president shows she can get things done.

Both Lightfoot and Preckwinkle have said they’re opposed to current proposals for a taxpayer subsidy of as much as $1.3 billion for Lincoln Yards, a development along the North Branch of the Chicago River with 6,000 planned housing units.

Lightfoot vowed in a recent interview to hold up payments for the project if the City Council approves the subsidies before the new mayor takes office in May. Preckwinkle said she too would like to slow the project.

For now, she said, “I’m focused on April 2.”

And that’s when things get truly interesting: After months of visiting neighborhoods around the

city, the new mayor will have to start showing she can fix them, too.

ProPublica Illinois is an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force. Sign up for The ProPublica Illinois newsletter for weekly updates.

Promises, Tamales and Even Truth-telling: Chicago’s Mayoral Race Hits the Final Stretch

Maria Hadden and former Cook County Clerk David Orr celebrate. [Jonathan Ballew/Block Club Chicago]

Maria Hadden and former Cook County Clerk David Orr celebrate. [Jonathan Ballew/Block Club Chicago]The scene hardly had the look of history being made. On an Election Day with low turnout, the voting booths stood empty. Outside, the surrounding blocks in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood were mostly quiet except for the sound of the bitterly cold wind.

On a nearby corner, Maria Hadden, the challenger for alderman of the city’s 49th Ward, waited to greet voters. Finally, a compact man in a heavy coat approached. He proudly told Hadden he had lived in Rogers Park for 30 years and was going to vote for her. They shook gloved hands.

In Hadden’s view, the race came down to whether residents felt their neighborhood would remain vibrant and affordable.

“Will we keep our economic and racial diversity?” she said. “Is the current leadership able to maintain that, or do we need new leadership?”

That evening, as totals streamed in, it became clear that voters demanded a change. Hadden overwhelmed Joe Moore, a 28-year incumbent, with 64 percent of the vote. She became the first openly queer black woman elected to the City Council, and one of the first black aldermen ever to come from the North Side.

Hadden’s victory was widely seen as one of the biggest upsets in Tuesday’s elections. But it actually reflects broader local and national political trends in the battle over the future of the Democratic Party.

Residents across Chicago worry they can no longer afford to live or invest in the city. As Mayor Rahm Emanuel tries to win approval for several massive new development projects before he leaves office in May, many voters are outraged at the idea of using public money to subsidize them. At the same time, residents in some neighborhoods remain desperate for development. Organizers north and south are campaigning to lift a state ban on rent control and build more affordable housing.

The 14 candidates for mayor all agreed on one point: To confront these challenges, Chicago didn’t need anyone like Emanuel. Most tried to distance themselves from his record of school closings, Wall Street campaign contributions and insider ties, touting themselves as progressives.

Of course, the two top finishers have their own ties to the political establishment. Toni Preckwinkle is the Cook County Board president and chair of the county Democratic Party. She also accepted fundraising help from 50-year Alderman Ed Burke, of the 14th Ward, who’s facing federal extortion charges. Preckwinkle has since repudiated Burke, who was re-elected despite his legal problems. Lightfoot, meanwhile, served in the mayoral administrations of Emanuel and his predecessor, Richard M. Daley.

Still, Preckwinkle and Lightfoot both tout their work on criminal justice reform, and they vow to pay attention to long-neglected parts of the city.

And as black women, they offer an obvious, visible break from the past. Chicago has elected one woman and one black man as mayor, but it has never been led by a woman of color. That 182-year streak is about to end.

Months ago, Moore sensed that his re-election bid in the city’s far northeast corner could be tough. He watched from afar as 28-year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez toppled another Joe, longtime U.S. Rep. Joseph Crowley, in a diverse, liberal New York City district not unlike the 49th Ward. In the age of President Donald Trump, Democrats seen as compromising or shopworn are sometimes viewed as part of the problem.

Moore first won office in a runoff in 1991. For the next 20 years, he was one of the City Council’s leading critics of Daley. From 2007 to 2011, Moore sided with the mayor on just 51 percent of divided roll-call votes, the lowest rate in the council, according to an analysis by Professor Dick Simpson and other researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

But when Daley retired and Emanuel took the reins, Moore became one of his closest council allies and his reputation as an independent withered. From 2017 to 2018, Moore voted with the mayor 98 percent of the time.

As Tuesday’s election neared, Moore reminded constituents of his progressive accomplishments: He helped bring community policing to Chicago; pioneered participatory budgeting, in which residents get to vote on how to spend infrastructure funds; and added affordable and public housing to the ward.

Hadden criticized Moore’s alliance with Emanuel. She targeted him for accepting campaign contributions from developers and landlords while many residents struggled to remain in the gentrifying area.

By Tuesday afternoon, Hadden thought she had a chance.

“But if nothing else, we’ve got new people voting, new people involved in the campaign, and we’re going to keep organizing,” she said. “In some ways, we’ve already won by putting the community’s vision first.”

Within a few hours, she had won the election, too

ProPublica Illinois is an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force. Sign up for The ProPublica Illinois newsletter for weekly updates.

Chicago’s Election Signals Break from the Past — in Wards and at City Hall

<span data-mce-type="bookmark" style="display: inline-block; width: 0px; overflow: hidden; line-height: 0;" class="mce_SELRES_start">

As she drove through her South Side ward one morning last month, Alderman Pat Dowell slowed up alongside a business on the corner of Prairie Avenue and 51st Street. The owners of the business wanted to hang a sign on the Prairie side of the building, “but I’d rather not have it on a residential street,” said Dowell, who has led the 3rd Ward since 2007. In her view, the sign would need to be on 51st, like the other signs on the block, so the area had a consistent look.

She saw it as an example of why she and her 49 City Council colleagues have so much power over their wards, down to their alleys and sidewalks.

Residents “need to have a go-to person, someone you can expect to address your issue,” Dowell said. “That person needs to be on the ground with you.”

From 2011 through 2018, Dowell was the chief sponsor of more than 900 separate ordinances in the City Council, most of them pertaining to such hyperlocal issues as business sign permits, driveway alley access and parking meter hours for single addresses or blocks.

That volume of ward-specific legislation is typical for Chicago aldermen. Dowell and others have fought for more oversight of city government. But the city’s legislative branch is largely consumed with processing small-bore and neighborhood administrative matters, with few aldermen taking the lead on issues beyond their ward boundaries, a ProPublica Illinois analysis of more than 100,000 pieces of legislation has found.

The structure of the council has received new attention over the last several months, as the city’s political establishment has been rocked by scandals involving aldermen. In January, federal prosecutors charged Ald. Ed Burke, the council dean and Finance Committee chair, with trying to shake down a Burger King franchisee that needed building and driveway permits for a restaurant in his Southwest Side ward. Burke has said he is not guilty.

That was followed by reports that council Zoning Committee chair Ald. Danny Solis wore a wire to record conversations with Burke while Solis himself was under investigation for alleged corruption, including trading political favors for sex. Another retiring alderman, former police officer Ald. Willie Cochran, is slated to go on trial this year after being charged with extorting businesses in his ward that needed his support for development projects and licenses.

In response, outgoing Mayor Rahm Emanuel and candidates in the Feb. 26 election to replace him have proposed a series of ethics reforms.

But tinkering with some of the official rules of the council is unlikely to alter the way it works. That’s because it functions within a political structure that has become ingrained over decades, partly through favor-trading.

At the height of Chicago’s Democratic machine in the 1950s and ’60s, aldermen and ward bosses had patronage workers, known as precinct captains, who helped provide residents with garbage cans, tree trimming and other services. The residents were then expected to vote for favored candidates.

The current arrangement, said Scott Waguespack, alderman of the North Side’s 32nd Ward, is “just a little more sophisticated than the garbage can version.”

Except in rare instances, the City Council signs off on the mayor’s agenda, even letting the city’s executive pick its legislative leaders. In return, aldermen are allowed to reign over matters large and small in their wards, which some openly describe as “fiefdoms.” Businesses and residents have to call on their aldermen for help getting many city services they pay for with their taxes.

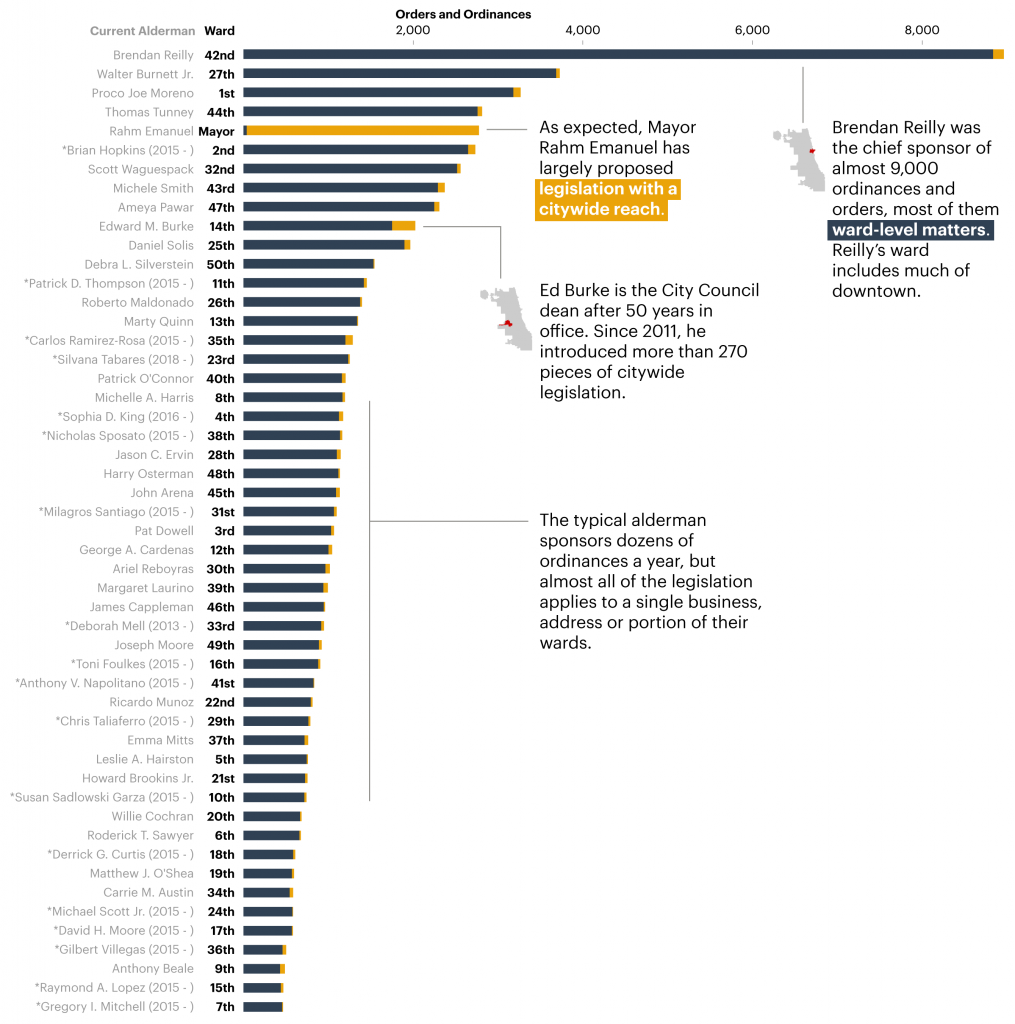

Legislative records, available through the online legislative information center maintained by the City Clerk’s office, show how the system works. From May 2011, when Emanuel was inaugurated, through the end of 2018:

- More than 75,000 proposed ordinances and orders were introduced to the council, an average of about 800 a month. Ordinances are local laws, while orders are binding dictates to other city departments.

- The council passed more than 90 percent of them.

- Most of the introduced ordinances pertained to single addresses or blocks, such as more than 8,800 ordinances authorizing specific sidewalk cafe permits and 3,500 for particular loading zones.

- In contrast, less than 10 percent of ordinances pertained to city budgets, taxes, contracts or citywide laws.

- The most active and powerful citywide legislator was the city’s top executive, Emanuel. He served as the chief sponsor of more citywide ordinances (about 2,700) than all the aldermen combined (about 2,100).

A spokeswoman for the mayor declined to comment. Aldermen, who are paid between $108,000 and $120,000 a year, say they’re doing the job residents demand of them.

“People think we have control over everything,” said Ald. Roderick Sawyer, chairman of the council’s Black Caucus and alderman of the 6th Ward on the South Side.

One morning last month, Sawyer and his chief of staff, Winston McGill, drove around the ward checking on trouble spots and constituent issues, from illegal dumping to problem businesses to parking concerns.

Sawyer pulled over next to a church on 71st Street and Union Avenue in the Englewood neighborhood. One of the church’s leaders had called his office to complain that a no-parking sign had just been posted on a stretch of the street where members had parked on Sundays for years. After taking a look, Sawyer didn’t see the need for the restriction. The sign was later removed.

A few minutes later, they stopped on the 6600 block of South Harvard Avenue. McGill noted that only a couple of cars were parked on the street at that time of day, yet some residents had asked to restrict the block to permit-only parking.

Sawyer was skeptical. He shook his head and laughed. “You see all the stuff we deal with as aldermen? You have to manage all these egos.”

Joe Moore, alderman of the far North Side’s 49th Ward since 1991, said the system helps residents get access to city services.

“We’ve always kind of done it this way,” Moore said. “You make us full-time legislators and we lose that hands-on approach. A little decentralization is not a bad thing. At a time people [when] feel very disengaged from politics and government, this grassroots style of governing does have its benefits.”

On a recent afternoon, Moore met with police leaders at the 24th District station to talk about several blocks in Rogers Park with safety issues. Back at his office, Moore sat down with a former neighborhood resident who asked for help with an area storage facility where his musical equipment had been stolen. Then residents of a nearby apartment building for seniors came in to talk with the alderman and an official from the Chicago Housing Authority about its plans for the property.

Aldermen do propose important legislation, Moore noted, such as an ordinance passed in 2015 that set aside $5.5 million to pay reparations to victims of police torture.

But since aldermen serve primarily as ward housekeepers, the pipeline of legislation at City Hall is cluttered with ordinances for permits and other single-address regulations.

Committee chairs and aldermen of downtown and North Side wards with busy commercial areas introduce the most legislation. They also tend to receive steady campaign contributions, including from people and businesses that need their help.

From 2011 through 2018, Brendan Reilly, alderman of downtown’s 42nd Ward, ranked first in sponsoring legislation. He introduced more than 8,500 ordinances; all but about 100 involved permits, traffic and other local matters.

Reilly said his office has to review so many permits and ordinances that he raised campaign funds to hire five extra staff members in addition to the three already paid for by the city budget.

That’s not an ideal situation, since it means privately paid workers are doing public work. In 2016, an aide paid out of Reilly’s campaign funds resigned after media reports revealed that her consulting firm had also lobbied for developers. Reilly said none of that work involved projects in the 42nd Ward.

Though his office speeds through “99 percent” of permit applications and renewals, the other 1 percent require a closer look, perhaps because the applicants haven’t complied with the terms of their permit, or they haven’t been good neighbors, he said.

Reilly said he’s all for streamlining permit renewals or taking some of the administrative work out of aldermen’s offices.

“But there would be pushback from residents,” Reilly said. “Just short of blaming aldermen for the weather, we’re expected to be accountable for everything else in the ward.”

While aldermen are focused on ward issues, Chicago mayors have seized control of the legislative and oversight process at City Hall.

As in Congress and other lawmaking bodies, legislation introduced to the City Council is typically assigned to a committee before it goes before the whole. The council has 16 committees, covering areas from aviation to zoning. Under the council’s own rules, aldermen are supposed to determine their own committee assignments and leadership.

But that’s not how it works. Dating back at least to the tenure of Mayor Richard J. Daley from 1955 to 1976, the mayor has taken control of picking committee chairs and assignments.

First-term Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa said Burke asked him and other freshmen to fill out a form listing their committee preferences during an orientation session the council dean led in 2015. Ramirez-Rosa, alderman of the Logan Square-based 35th Ward, didn’t get any of his picks.

Instead, Ramirez-Rosa ended up on committees that rarely meet, like Health and Environmental Protection, and some that do little but sign off on ward-level legislation, like Pedestrian and Traffic Safety.

“All we’re doing is rubber-stamping what colleagues have put together,” he said.

In contrast, Moore serves on the powerful Finance and Budget committees. For 20 years, when he regularly criticized former Mayor Richard M. Daley, Moore was largely shut out of power. But after he allied himself with Emanuel in 2011, the mayor picked him to lead the Human Relations Committee. Four years ago, Moore received a promotion of sorts by being named chair of the Housing Committee, which has a larger staff and budget.

By deferring to the mayor to pick committee chairs, aldermen have made the process of picking their leaders easier, Moore joked. “You only had to lobby one person instead of the whole council,” he said.

Ald. George Cardenas of the 12th Ward, chair of the Committee on Health and Environmental Protection, has helped pass ordinances pushed by Emanuel to crack down on illegal dumping and the use of dangerous chemicals in dry cleaning.

But Emanuel has repeatedly nixed proposals from Cardenas. Among them: a 2012 resolution calling for hearings on the health impacts of sugary beverages and the possibility of taxing them. Cardenas said he just wanted to start a conversation, given the nation’s obesity epidemic.

Aides to the mayor told him not to hold the hearings, Cardenas said. “The administration didn’t think it was the right time,” he said, especially since the soft drink industry was against it.

Instead, a few months later, in November 2012, Emanuel announced that the Coca-Cola Foundation would donate $3 million to fund health programs in the city. Subsequent donations from Coca-Cola have funded improvements in city parks.

Cardenas said aldermen need to pick their own committee chairs, perhaps based on seniority, to allow them to be more independent.

“For the last five mayors, the mayor handled it because the aldermen gave it away,” he said.

One of the most powerful council posts is the chair of the Committee on Committees, Rules and Ethics. Under council rules, the chair has the power to decide where to send each piece of introduced legislation. In 2013, Emanuel chose Michelle Harris, alderman of the South Side’s 8th Ward, for the job.

Since then, Harris has held dozens of pieces of legislation in the committee without bringing them up for a vote, including proposals for ethics training for city contractors; additional oversight of the city’s investments; and a plan to livestream committee hearings.

“Michelle Harris is [Emanuel’s] workhorse to stop legislation,” Waguespack said. “It boils down to her doing the bidding of the mayor, and the mayor having a policy that’s essentially, kill anything that would challenge his or Burke’s authority.”

Asked about getting direction from the mayor, Harris said she sometimes acts as a “go between” during negotiations with aldermen. But she said the fate of legislation depends on whether supporters can show her they have the votes before their public meetings. Harris noted that under council rules, aldermen can undertake a multi-step process to force legislation out of a committee if 26 of them back it.

Still, she said, she prefers an “informal” approach to determining when legislation has support. “I’d rather sit down and talk about it,” she said.

Other aldermen say taxpayers deserve a more open process.

“It would seem to me that she supports an approach to government that’s done in a back room,” 45th Ward Ald. John Arena said. “There’s an attitude among some that you only put it forward in committee if it’s going to pass. Whereas we think you put forward ideas and you discuss them, and it might take two meetings to pass because the whole point is to go over issues.”

Both the size and priorities of Chicago’s City Council are unusual. New York City has a 51-member council — the only one from a major city that’s comparable in size to Chicago’s. New York also has more than three times the population. While its council members provide constituent services, they spend considerable time and political capital on oversight of the mayor and city departments, said Bruce Berg, a political science professor at Fordham University. For example, the New York City Council holds budget hearings every six months that often result in significant changes.

“In that way, they’re almost an equal partner to the mayor,” Berg said. Since New York council members are limited to two consecutive four-year terms, “it gives members the incentive to make a splash while they’re there.”

In Chicago, Budget Committee chair Ald. Carrie Austin oversees two weeks of public hearings each year on the budgets proposed by the mayor. For three decades, the mayors’ budgets have passed the council overwhelmingly, usually with only minor tweaks.

But Austin said aldermen do vet the mayor’s budgets and other legislation, though it usually happens in closed-door meetings.

“By the time it goes to the committee or the council, we’ve worked out the kinks,” Austin said.

Aldermen know that their work in the council is not their top priority, added Austin, who has represented the 34th Ward on the far South Side since 1994, when Daley appointed her to finish the term of her late husband.

“The things we do down here, they’re important,” Austin said, “but not as important as what’s going on in the ward."

ProPublica Illinois is an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force. Sign up for The ProPublica Illinois newsletter for weekly updates.

At Chicago City Hall, the Legislative Branch Rarely Does Much Legislating

This still image taken from police dash camera video, eventually released by the city in November 2015, shows Chicago teen Laquan McDonald just prior to being shot by Officer Jason Van Dyke on Oct. 20, 2014. (Chicago Police Department)

This still image taken from police dash camera video, eventually released by the city in November 2015, shows Chicago teen Laquan McDonald just prior to being shot by Officer Jason Van Dyke on Oct. 20, 2014. (Chicago Police Department)<span data-mce-type="bookmark" style="display: inline-block; width: 0px; overflow: hidden; line-height: 0;" class="mce_SELRES_start">

ProPublica Illinois reporter Mick Dumke looks at the state’s political issues and personalities in this occasional column.

From the day Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke shot and killed Laquan McDonald in 2014, city officials have worked to keep records from the shooting secret.

Yet when journalists and other citizens sought help from the office of Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan — which is responsible for interpreting and enforcing the state’s Freedom of Information Act — the agency did little to ensure the materials were released to the public.

Over the last four years, reporters and citizen activists have filed at least 10 appeals with the attorney general’s office after Chicago officials blocked their requests for video, police reports, emails and other materials tied to the shooting, according to documents maintained by the office.

But most of the McDonald-related appeals dragged on for months or years — including one filed in 2015 that wasn’t closed until this fall — before the attorney general’s office took action. When it did, the city repeatedly ignored its decisions and resisted producing any records.

Together, the cases expose critical flaws in the Illinois Freedom of Information Act and its enforcement under Madigan, who helped write the current version of the law. She is leaving office in January after 16 years. Her successor, Kwame Raoul, has vowed to make FOIA enforcement a priority.

Maura Possley, a spokeswoman for Madigan, blamed “government offices that steadfastly refuse to follow FOIA” for blocking the release of records and hampering the public access counselor. The PAC is the office Madigan and her staff launched in 2010 to handle open-government cases.

“Under the statute, the goal of the Public Access Counselor is to help resolve disputes as an alternative to court, not to litigate every matter,” Possley wrote in a statement. “In the matter involving the Laquan McDonald shooting, it is clear that the Chicago Police Department was not going to release information without a court order.”

A spokesman for the city’s Law Department said the city receives thousands of FOIA requests a year and works to provide public records “in a timely manner.”

“As part of state law, requesters have several options if they feel their response should include additional or unredacted records, and the city works to resolve these differences as quickly as possible,” the spokesman, Bill McCaffrey, wrote in a statement.

McDonald’s killing highlighted the crucial importance of opening government records to the public. In November 2015, a judge ordered the release of the now-infamous video showing Van Dyke shooting McDonald 16 times as the teen appeared to be walking away — contradicting what police reported.

That set off a chain of events leading to Van Dyke’s conviction this year of second-degree murder, the recent trial of three other officers for conspiring to cover for him and the announcement by Mayor Rahm Emanuel that he wouldn’t run for re-election. When the Trump administration refused to push for reforms to the Chicago Police Department, Madigan’s office sued to make sure the plan was backed by a federal court order.

But that all happened despite the attorney general’s FOIA enforcement, not because of it. In fact, the office’s FOIA decisions may have ended up delaying justice in the McDonald shooting and costing taxpayers money.

Here’s how.

1. The attorney general’s office rejected some FOIA appeals because of missed deadlines.

In January 2015, a producer for MSNBC submitted a FOIA request to the Chicago Police Department for copies of reports from the shooting and video captured by police car dashboard cameras. After a month, the department denied the request. Releasing the video could harm ongoing investigations into the shooting, police officials argued, and therefore the Freedom of Information Act entitled the department to keep it secret.

That April, a lawyer for NBCUniversal, the parent company of MSNBC, appealed to the PAC.

“The CPD has failed to provide any factual basis or explanation for its nondisclosure,” the NBC lawyer wrote.

The PAC is barraged with appeals of FOIA requests denied or ignored by the Police Department — more than 2,500 since 2010, ProPublica Illinois found in an investigation published in October. Only the Illinois Department of Corrections, inundated with requests from inmates, accounts for more.

On May 6, 2015, the PAC informed NBC that the network had missed a deadline to file its appeal within 60 days of being denied. As is required under the law, the case was closed.

2. The attorney general’s office then missed its own deadlines and allowed government bodies to ignore the law.

By then, other journalists were trying to get copies of the dashcam video, especially after city officials discussed it before the City Council signed off on a $5 million settlement with McDonald’s family.

In May 2015, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal requested the video and reports from the shooting. Police officials waited six days to respond even though the denial letter was almost identical to those sent to MSNBC and others seeking the records.

That June, a lawyer for the Journal asked the PAC for a review.

“Public scrutiny of such records is essential to maintaining confidence in the administration of justice,” attorney Jacob Goldstein wrote.

Goldstein had met the deadline for filing an appeal. Under the Freedom of Information Act, the PAC then had 60 days to issue a binding opinion, a ruling that all parties would have to follow unless they challenged it in court.

But the office showed little urgency. While requesters face a firm deadline for filing appeals, the law gives the PAC discretion in deciding how long to give government bodies to respond. Officials in the attorney general’s office say the law could be strengthened, though in this and many other cases, they chose to wait months for replies.

“CPD has not responded, and currently has a backlog of requests due to staffing issues,” an attorney in the PAC’s office wrote to Goldstein in July 2015. “I have requested that they expedite this response, and it will be forwarded to you upon receipt.”

Goldstein noted that the Police Department could be found in violation of FOIA if it failed to respond. The attorney in the PAC’s office didn’t reply.

In the meantime, others kept pushing for copies of the shooting video. MSNBC filed a new request with the Police Department and, after it was denied, appealed to the PAC. The case stalled just as the Journal’s did.

The Police Department also denied a request for the video from independent journalist Brandon Smith and activist William Calloway. Instead of seeking a review from the PAC, Smith hired attorney Matt Topic and sued the department. Smith said he was able to file the lawsuit because he didn’t have to pay Topic up front; requesters can collect attorneys’ fees from government bodies found to have violated FOIA.

Topic has worked with ProPublica Illinois and many other news organizations on FOIA cases.

“I had already looked into the PAC and realized it was not as effectual as I needed to get stories out,” Smith said in an an interview.

Smith’s lawsuit attracted widespread media coverage; a judicial ruling was scheduled for November 2015.

Then, on Nov. 6, with the court hearing imminent, the PAC finally weighed in: The Police Department had improperly denied the Journal’s FOIA request. Plus, it had failed to cooperate with the PAC’s review, a point the Journal’s lawyer had made months earlier. Officials in the attorney general’s office say the timing of the decision had nothing to do with the court case.

The PAC urged the department to release the dashcam video and police reports. But after the PAC had missed the deadline for a binding order, the opinion was merely advisory.

That outcome wasn’t unusual. The PAC has issued binding opinions in less than half of one percent of the appeals it’s reviewed. And many of the PAC’s advisory opinions are simply ignored by government bodies — including, in this case, the Police Department.

The department couldn’t ignore the Nov. 19 ruling from Cook County Judge Franklin Valderrama, who ordered the department to release the dashcam video. The judge’s decision didn’t mention the opinion from the attorney general’s office.

The Journal, MSNBC and other media organizations received copies of the video when the city released it a few days later. Still, it was this October, almost three years later, when the PAC followed up with MSNBC about its second, long-stalled appeal, records show. A lawyer for the network confirmed that it already had the video, and the case was officially closed.

3. The attorney general’s office repeatedly declined to use its full authority to order the release of public records.

After the release of the video, the city received a flurry of new FOIA requests related to the shooting. On New Year’s Eve, when audiences are often tuned out, the city released hundreds of pages of emails about the McDonald shooting. Many exchanges among top city officials were blacked out. In January 2016, NBC 5 producer and investigator Don Moseley asked the PAC to review the redactions in just one of the emails, arguing that “the public has an inherent right to know what senior officials in the office of Mayor Rahm Emanuel knew at the time regarding video of a fatal police shooting.”

The PAC sided with Moseley that spring and urged the city to turn over an unredacted copy of the email. But it was only an advisory opinion, and weeks passed before Moseley and his colleague, reporter Carol Marin, finally saw a full copy of the email.

It left them wondering why the city had redacted it in the first place. The message was a recitation of facts, including the name of the attorney hired by McDonald’s family, but it included nothing damning, revealing or even newsworthy.

“We looked at it and said, ‘Why would you fight that one?’” Marin said. “It was wallpaper.”

4. When the attorney general’s office did issue a binding opinion, it was challenged in court.

In January 2016, a producer for CNN sent the Police Department a FOIA request for emails about the shooting from Van Dyke, his partner and other officers. In addition to official police emails, CNN sought messages from private email accounts.

That summer, after CNN appealed to the PAC, police officials conceded that they hadn’t attempted to look through the personal email accounts of Van Dyke or the other officers. They argued they shouldn’t have to, since those messages weren’t public records.

The PAC disagreed. In August 2016, the office issued a binding opinion in CNN’s favor, ruling that emails on personal accounts that pertain to public business are public. The Police Department was ordered to search the officers’ personal email accounts.

Instead, the city sued — and, a year later, in September 2017, lost.

“Government operations in a free society must not be shrouded in secrecy,” Cook County Judge Pamela McLean Meyerson wrote in her ruling.

Yet CNN never received the emails at the center of the battle. Last March, CNN went back to court to force the city to comply with the judge’s order. But the city argued that all it could do was ask the officers to have their personal email accounts searched. Either individually or through attorneys, each officer either refused, denied having any relevant messages or simply ignored the request.

5. As the city continues to block many FOIA requests, some journalists are bypassing the attorney general’s office and turning to the courts — which costs taxpayers money.

This month, Lucy Parsons Labs, a nonprofit focused on police accountability and transparency, sued the Chicago mayor’s office for refusing to release a copy of its plan to respond to potential protests after the Van Dyke verdict.

Since 2013, as more journalists have turned to the courts for help, the city has paid more than $1 million in attorneys’ fees in FOIA cases.

Freddy Martinez, the Lucy Parsons director, says he sees little point in turning to the attorney general’s office because the process takes too long and often doesn’t produce records.

“Going to the PAC is just not an option for us anymore,” he said. “Our main strategy is always to sue for records. And it’s a shame because it costs taxpayers money.”

The Laquan McDonald shooting keeps exposing critical flaws in Illinois’ Freedom of Information Act

J.B. Pritzker declares victory. [Twitter/JBPritzker]

J.B. Pritzker declares victory. [Twitter/JBPritzker]ProPublica Illinois reporter Mick Dumke looks at the state’s political issues and personalities in this occasional column.

The official slogan of the state of Illinois remains “Land of Lincoln,” and lots of Republicans still live here. But it’s no longer the land of his political party. The GOP isn’t winning many elections, which is generally considered the purpose of a political party.

And that brings us to the bluebath that happened this week, when Illinois Democrats seized two congressional seats that for decades had been held by Republicans, ousted one-term Gov. Bruce Rauner, easily held onto every other statewide office, solidified control of the General Assembly and toppled the Cook County commissioner who chairs the state GOP.

In short, it wasn’t a great night here for the Republicans.

“The land of Lincoln and Barack Obama,” J.B. Pritzker called the state during his speech after beating Rauner. He didn’t need to point out that Obama is a fellow Democrat.

Here are a few observations and thoughts on what happened and what might happen next:

Rauner didn’t lose all his friends — but he certainly didn’t make enough new ones.

Four years ago, voters were weary of state leaders’ lack of fiscal discipline — high taxes and billions of dollars of debt will do that — and Gov. Pat Quinn didn’t inspire confidence. Rauner, a millionaire businessman, promised to fix the government and stand up to Michael Madigan, the state House speaker, Democratic Party chair and most powerful figure in state government.

Rauner received about 1.8 million votes to 1.7 million for Quinn, who didn’t concede until the day after the election.

After four years of bitter feuding with Madigan, including a two-year budget impasse, Rauner still received more than 1.7 million votes Tuesday. Unfortunately for him, about 2.4 million people voted for Pritzker.

Emblematic was DuPage County, a GOP stronghold. In 2014, Rauner cleaned up there with 61 percent of the vote. This time, though he received close to the same number of actual votes, he lost the county to Pritzker.

Pritzker gave out more goodies than Rauner.

In 2014, Rauner didn’t just win his party’s nomination — he all but purchased it, just as he’d bought and sold businesses when he was leading a private equity firm. In the two years leading to his election as governor, Rauner poured about $28 million of his personal wealth into his campaign fund, records show. At the same time, Rauner, his campaign, and his wife, Diana, gave more than $9 million to other GOP candidates and committees across Illinois.

As he moved toward his re-election bid, Rauner was even more generous, putting $50 million into his campaign fund and distributing almost $16 million to other Republicans.

The strategy, and the money, were so convincing that Pritzker decided to do the same thing, but on a scale that made Rauner’s giving look chintzy by comparison. Pritzker pumped more than $171 million of his own money into his campaign fund, and he handed out about $24 million to other Democratic committees and candidates, including the DuPage County Democratic Central Committee.

Now Democrats won’t have Rauner to kick around any more.

As the state budget crisis stretched more than two years, Democrats blamed Rauner, and much of the public sided with them. Rauner conceded defeat Tuesday less than an hour after the polls closed, ending the contentious, expensive campaign so suddenly that some of the governor’s critics seemed unprepared to talk about what they’ll do once he’s out of the way.

Thirty minutes after the race was called, state Comptroller Susana Mendoza took the stage at Pritzker’s election night gathering and introduced herself as “your truth-telling fiscal watchdog who was not afraid to stand up to the biggest bully in this state, Bruce Rauner!” Mendoza, who is weighing a run for mayor of Chicago, then celebrated Rauner’s defeat by shouting, “You’re fired!” — a line long associated with Donald Trump’s days on the reality show “The Apprentice.”

The Democrats still weren’t done ripping on Rauner. An hour after he conceded, Sen. Richard Durbin ridiculed the governor for riding his motorcycle around the state while wearing a leather vest. Downstaters, he said, “can spot a phony a mile away.”

Then, on Wednesday, Madigan took a shot at Rauner in a press release, which was especially striking because he rarely issues statements or otherwise communicates with the public. “Last night’s election results definitively proved that the Rauner Republican playbook of attempting to make the entire 2018 election a referendum on Speaker Madigan, to distract from Republicans’ record, is a failure,” the release said.

Instead, the Democrats managed to turn the elections into a referendum on Rauner and Trump. Voters now hope the Democrats will be half as good at addressing the state’s budget and debt problems as they were at mocking the governor.

Now Republicans won’t have Rauner to kick around any more.

Democrats disliked Rauner from the beginning, but for many conservative Republicans it took a couple of years. After he signed legislation expanding access to abortion and protections for undocumented immigrants, the right wing of the party launched its own attacks. To critics like state Rep. Jeanne Ives, Rauner had abandoned the party’s base, proving once again that the Democrats will always win if Republicans “surrender” and move to the center.

Still, Ives came up short when she challenged Rauner in the GOP primary. So have most of the conservative candidates backed by her allies and funders. For example, of the top 20 candidates supported this election cycle by the Liberty Principles political action committee, run by Ives ally Dan Proft, 16 lost. Among them: state Rep. Peter Breen, the GOP floor leader in the state House, who represents a district in DuPage County.

The election is over. The next elections have begun.

Now in power, Democrats will work to move the state to the left.

“Are you ready to fight for Illinois?” Pritzker said during his victory speech, and his supporters shouted that they were.

But as the GOP regroups, Ives and her allies are funded by their own really rich guys, and they’re eager to keep pushing the party and the land of Lincoln to the right.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emanuel isn’t running for re-election in February, and 17 would-be successors, give or take a few, are hoping to get on the ballot. All 50 seats in the City Council are also up for election. Voters were tuned in even before the ballots were counted Tuesday.

“They’re glad about the mayor’s race,” said Barbara Kendricks, who was talking with voters and handing out flyers Tuesday outside a polling place in the South Side Kenwood neighborhood. “The mayor, we want him out.”

The election is over. And now the next elections begin.

[Susie Cagle. special to Pro Publica]

[Susie Cagle. special to Pro Publica]Since he first entered politics as a candidate five years ago, Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner has pledged his commitment to open government.

As he put it during a debate last week with challenger J.B. Pritzker before the Chicago Sun-Times editorial board: “Transparency is great.”

As he fights for re-election, making the declaration is a great move on Rauner’s part — and an easy one. Voters are demanding more and more information about what their governments are doing with their tax money, and every candidate at every level is wise to speak in favor of sharing it with them.

But what Rauner means when he vows to be transparent isn’t so clear, given his administration’s habit of fighting against the release of information. The governor’s office won’t even disclose how often it blocks the release of records sought by the public.

From January 2017 through this June, the governor’s office received more than 500 requests for records under the state Freedom of Information Act, according to a log released to me in response to a FOIA request. The log shows the office received requests from journalists, unions, businesses and independent citizens who wanted copies of the everything from Rauner’s schedule to emails from first lady Diana Rauner.

Yet the governor’s office wouldn’t provide me records showing whether it granted or denied the requests, arguing it wasn’t obligated to under the law.

“Please also be advised that the Governor’s Office is not required to answer questions or generate new records in response to a FOIA request,” one of the governor’s attorneys wrote in a letter.

In other words, Rauner’s lawyer was arguing that his office didn’t have to reveal how it responded to FOIA requests because it doesn’t have those records on hand. That means the governor’s office kept a detailed log of every FOIA request it received, who made it, what it was for and when a response was due — but claimed it didn’t track whether the office ever provided the information or complied with the law.

Either the office isn’t being transparent or it’s not keeping good records.

Even so, the response to my request was more forthcoming than what another Chicagoan, Sarah Jackson, got last year when she asked the governor’s office for a FOIA log: nothing at all. The office never responded to her, according to a summary of the case by the office of Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s public access counselor, which handles FOIA disputes.

When Rauner’s office didn’t acknowledge her request within two weeks, Jackson notified the PAC, which tried to find out what had happened. But Rauner’s office didn’t respond to those inquiries either. In December, the PAC issued a binding opinion ordering Rauner’s office to produce the log.

Jackson’s FOIA request was one of more than 40 appealed to the PAC from January 2017 through this June after Rauner’s office denied them, records from the attorney general show. In addition to Jackson’s case, the PAC ruled three other times that the governor’s office had violated FOIA. On at least 16 other occasions, the governor’s office responded or reached an agreement with the requester after the PAC got involved. Most of the other cases were closed for administrative reasons. The PAC determined Rauner’s office had acted properly in just one of the disputes.

As I found in a recent investigation, the PAC’s office is backlogged with FOIA appeals that often take months or even years to resolve. One of the reasons it gets so many cases is that public bodies around the state resist such requests.

Ann Spillane, the attorney general’s chief of staff, said the obfuscation starts with Rauner.

“We have a governor of Illinois who actively tries to undermine the FOIA,” she said.

But Patty Schuh, a spokeswoman for Rauner, said his administration remains committed to transparency and devotes considerable resources to complying with the law.

“Our teams spend hundreds of hours each week reviewing documents to respond to FOIA requests as completely as possible and in a timely manner,” she wrote in an email. “We’ve produced hundreds of thousands of pages of responsive documents. In addition, the volume produced by individual state agencies under the Administration could number in the millions.”

Schuh described an office barraged with FOIA requests, including many that take long hours to process. She said the governor would be willing to work on “improvements” to the law, which was first passed in the 1980s.

“The law doesn’t adequately account for the current reality that some government bodies, including our office, add hundreds of thousands of emails each year to their records, if not millions,” Schuh said.

But Rauner wasn’t very sympathetic to the burden the law placed on his predecessor, Pat Quinn, portraying him four years ago as a product of the secretive Democratic machine. He promised to bring a new level of openness to state government if elected.

After taking office in 2015, though, Rauner’s administration began arguing that it was exempt from many FOIA requests, including for basic records such as his daily meeting schedules. In September of that year, the PAC ruled against the governor, concluding his calendars were indeed public records.

His office then stopped naming the people he met with, instead using only their initials on the calendars.

Rauner also repeatedly fought to keep state officials’ emails secret. Last week, the PAC issued another binding opinion that said the emails are public records and releasing them doesn’t place an undue burden on the office.

Much as Rauner once went after Quinn, Pritzker has spent the last year hammering Rauner for concealing key decisions and scandals within his administration.

During the Sun-Times debate, for example, Pritzker accused Rauner of flouting FOIA by redacting emails that reporters sought while investigating a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease at the Illinois Veterans’ Home in Quincy.

“They were blacked out because he didn’t want to let people know what was going on, which was an effort to cover their butts, to make sure that they weren’t held accountable,” Pritzker charged.

Rauner denied any wrongdoing. Instead, he attacked Pritzker for not revealing details of his tax plan, and for getting his own tax breaks after removing toilets at his Gold Coast mansion.

The governor had a point: Neither move was a model of transparency.