Bio

Investigative reporter @ProPublicaIL, Chicago-based arm of @ProPublica. Formerly of @chicagotribune. Always a lover of chocolate.Photo illustration by Alex Bandoni/ProPublica. Source Images: Roseland Hospital by Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Chicago Sun-Times via AP, Background by Getty Images.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

An Illinois lawmaker said she will propose legislation to require hospital employees to report suspected patient-on-patient sexual assaults to law enforcement.

Legislator pushes for law requiring Illinois hospitals to report all assaults to police

With schools, day care centers and preschools around Illinois shut down as part of statewide efforts to contain the spread of the coronavirus, calls to the Department of Children and Family Services’ abuse and neglect hotline have dropped dramatically over the past week.

But child welfare experts and others don’t believe this decline reflects a decrease in abuse; on the contrary, many fear that children are now at a greater risk of being hurt as families, many facing additional stress over work and health issues, hunker down in isolation.

Because children aren’t in school or child care, the teachers, social workers and counselors most likely to spot signs of abuse and who are required by state law to report those allegations, can’t.

“Unfortunately, we know there aren’t changes in the number of children being abused or neglected,” DCFS spokesman Jassen Strokosch said.

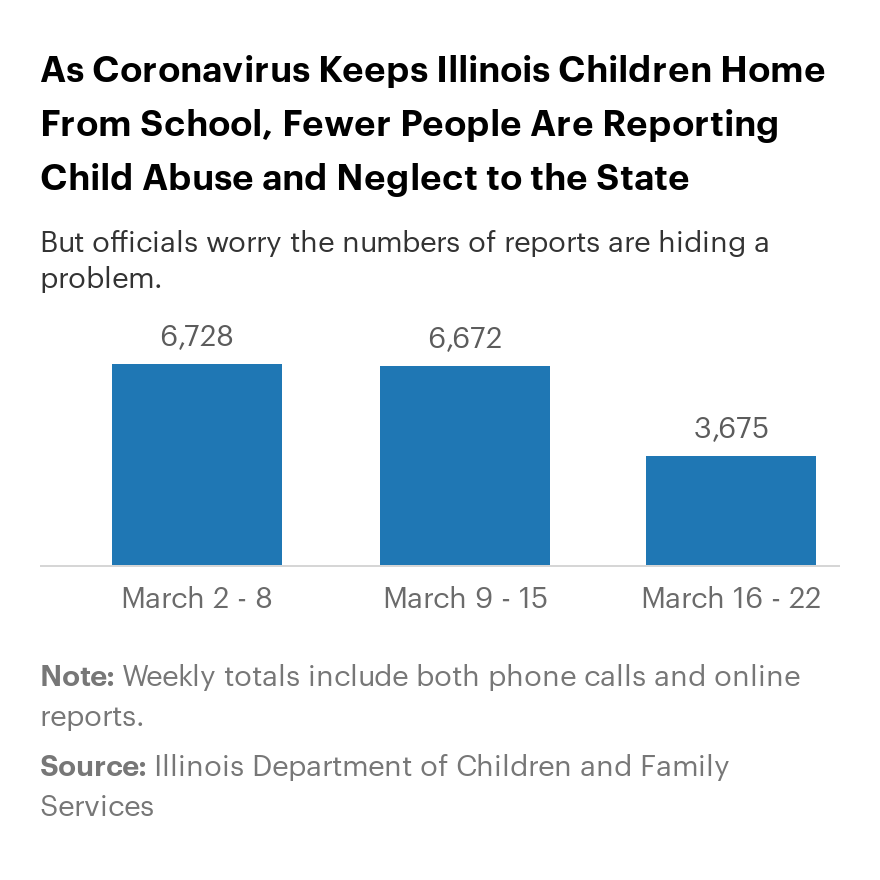

During the week of March 9, before Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s order to close all schools, DCFS received 6,672 reports of abuse and neglect via the statewide hotline — 91 percent by phone and 9 percent through an online reporting system.

Pritzker’s school shutdown order went into effect March 17, and as parents began to lose their jobs or were ordered to work from home, the number of hotline reports plummeted by 45 percent to 3,675 that week, the DCFS figures show.

The hotline receives about 950 calls a day during peak times — about 6,650 a week — according to a 2019 report.

The steep drop comes at a perilous moment for families. Child welfare experts worry that the uncertainty and anxiety caused by the coronavirus and the impact it will have on people’s jobs, their ability to pay bills or make rent will put children in increased danger at home.

“The risk of child abuse and neglect just shot through the roof,” said Kate Gordon Eller, an attorney and founder of The Gordon Foundation, a Chicago-based child welfare nonprofit. “The stress on everybody is growing every day. People are not able to maintain the same income. Then you have all these kids who are home all day. And it’s indefinite.”

The situation may worsen in the weeks to come. Strokosch said he expects to see the number of reports of abuse and neglect tumble further in the next week.

Following Pritzker’s shelter-at-home order, which went into effect on Saturday, children are even more removed from the public eye, likely spending less time outside and with emergency access to doctors and dentists, who are designated as mandated reporters because they are legally required to alert the state when they suspect abuse or neglect.

The system, he said, relies on people notifying the agency of these concerns, though DCFS has faced criticism when the hotline wasn’t able to accept calls as they came in and was hampered by inefficiency and inadequate technology. School officials report allegations of abuse to DCFS more than most other categories of workers, including police or medical personnel, Strokosch said.

“If we had a family who was in crisis before, the additional pressure of COVID-19 puts them at greater risk,” Strokosch said.

Research shows that the risk of child abuse rises in times of economic stress, said Char Rivette, executive director of the nonprofit Chicago Children’s Advocacy Center. And reports of abuse and neglect typically drop during the summer when children are at home or when other events keep children away from school, such as the Chicago Public Schools teachers’ strike late last year, Rivette said. But the unprecedented nature of the current crisis has left workers particularly uneasy.

“We’re very concerned,” Rivette said. “We know abuse happens in isolation, especially sexual abuse. All of these kids are staying home with family members, and those are the people most likely to abuse kids.”

The center, which works with Chicago police and DCFS to interview children in sexual abuse investigations, also has seen its case numbers drop dramatically. The office went from 10 to 15 cases a day to three to four, Rivette said.

In the meantime, Rivette said her organization and the dozens of other child advocacy centers across the state are working to provide information to parents to help lower tensions and protect children from sexual abuse, especially if additional family members have joined the household.

For parents who are “extremely stressed and worry they might abuse their children,” the Arlington Heights-based nonprofit Shelter Inc., recently added the number of the National Parent Helpline to its list of resources, said Patricia Cinquini, the communication and grant manager for the group that provides emergency shelter and other services for children and adolescents.

Last Tuesday, the first day children across the state stayed home following Pritzker’s order to close all schools, Cinquini wrote on the nonprofit’s website that she feared the social isolation of the shutdown, along with concerns about health, job security and other issues, could create “a perfect storm” leading to abuse.

Children and teenagers who are victims of abuse or neglect may not now be able to call for help because they are not alone or are more likely to be overheard, Cinquini said. Nor can they easily run away from an abusive home or seek shelter with friends.

“If they’re couch surfing, other families aren’t as willing to have them come to them,” she said. “So many of them are forced to stay in dangerous situations because they have no place to go.”

Teachers are doing their best to stay in touch with students who may be at risk, said Andrew Johnson, a social science teacher and college adviser at Westinghouse College Prep, a high school in Chicago’s East Garfield Park neighborhood. He said he has sent out individual emails checking on students but the majority have not responded. A few replied with two words: “I’m fine.”

“It’s paralyzing to think of all the situations that some of my students must find themselves in,” Johnson said. “And what can I do? Nothing. I feel powerless as an educator to be able to reach out to students effectively.”

Ryan Kinney, a counselor who works with Johnson at Westinghouse, said he has made hundreds of hotline reports to DCFS over the last decade. In the last week, he enlisted his colleagues and school principal to reach out to students he is most concerned about who didn’t respond to his initial emails.

But the process took days.

“God forbid it might be a life-or-death situation,” he said.

If he suspected the student’s situation to be dire while in school, he would alert Chicago police or DCFS. Without seeing his students, he has no way to know if a situation is deteriorating.

“That’s what keeps me up at night,” Kinney said, “What don’t we know is going on right now?”

DCFS’ Strokosch said the agency needs family members and neighbors now more than ever to report their suspicions to the hotline.

“Do not assume that someone else will report it,” he said. “You might be the only person seeing it.”

And if the reports come in, he said, child protection investigators will respond. Beyond that, he said, there’s little more DCFS can do.

Last Friday afternoon, longtime DCFS investigator Stephen Mittons sat in his car outside a red brick three-flat before he went inside to investigate an allegation of neglect that had come in earlier that day. In his pocket, he had hand sanitizer and a pair of latex gloves he had brought from home.

Mittons, who is also president of AFSCME Local 2081, the union for DCFS workers in Cook County, said school workers are the agency’s “eyes and ears” and often the first to notice a child with unexplained bruises. Now, he said, “we don’t have that teacher to see that the next day.”

But, he added: “We have a job to do. The world doesn’t stop.”

ProPublica Illinois is an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force. Sign up for The ProPublica Illinois newsletter for weekly updates.

Calls to Illinois’ child abuse hotline dropped by nearly half amid the spread of coronavirus. Here’s why that’s not good news.

Lydia Fu for ProPublica Illinois

Lydia Fu for ProPublica Illinois

The Acting Cook County Public Guardian filed a class-action lawsuit Thursday on behalf of hundreds of children and teenagers in state care who have been held in psychiatric hospitals after they had been cleared by doctors for release, calling the practice inhumane and unconstitutional.

The Illinois Department of Children and Family Services has a constitutional responsibility to ensure that children in the department’s care, whose lives are already marked by trauma, are not unnecessarily held in psychiatric hospitals, according to the lawsuit, which was filed in federal court in Chicago.

“The effects of holding children (beyond medical necessity) are heartbreaking at an individual level and staggering when multiplied among all the children who have been subjected to the practice,” the lawsuit claims.

The lawsuit follows a ProPublica Illinois investigation in June that found nearly 30 percent of children in DCFS care who were sent to psychiatric hospitals between 2015 and 2017 were held there after doctors had cleared them for discharge. The children were hospitalized for a collective total of more than 27,000 days, or nearly 75 years.

The unnecessary hospitalizations cost the state millions of dollars.

ProPublica Illinois found that DCFS spent nearly $7 million on medically unnecessary hospitalizations between 2015 and 2017. In addition, the lawsuit alleges that the state could have saved an additional $3.4 million if DCFS had discharged the children to the next most expensive placement.

The lawsuit, which seeks unspecified monetary damages, was filed on behalf of Cook County Acting Public Guardian Charles Golbert and names more than a dozen former patients, though it says hundreds of children ultimately will join the lawsuit. It named as defendants DCFS, the agency’s acting director, Beverly “B.J.” Walker, and previous directors dating to 2008, as well as other DCFS employees tasked with tracking or finding placements for children in psychiatric hospitals.

“It’s hard to imagine a more profound violation of a young person’s civil rights,” Golbert said. “It must stop.”

DCFS would not comment on the lawsuit but said finding placements for children is challenging. Some residential treatment centers and foster homes won’t accept children in psychiatric hospitals with serious mental or behavioral health conditions, said Neil Skene, special assistant to Walker.

The agency is working build additional services and reduce the need for hospitalization, Skene said, but the problem is part of a larger issue related to rebuilding the state’s mental health system.

“The availability of community resources and facilities to handle complex behavioral and physical health needs of children and teenagers is a serious need in Illinois,” Skene said. “This is a decades-long problem in Illinois that has now fallen to the current leadership of DCFS. We are at the deep end of a challenge within the healthcare system.”

The number of children being held beyond what is considered medically necessary has increased in recent years. In 2017, 301 psychiatric hospital admissions of children in DCFS care went beyond medical necessity, a sharp rise from 88 in 2014, according to DCFS figures.

The lawsuit, which does not use the children’s full names to protect their privacy, lists a litany of harmful emotional and psychiatric effects of prolonged hospitalizations. They include isolation, loss of liberty and schooling, and missing out on family connections. The children are subjected to a “dangerous environment” where some act out physically and sexually, according to the lawsuit.

“Lengthy hospitalizations tend to erase any gains made by children during the medically necessary portion of their stay, and over time many children exhibit more psychiatric distress than they presented with at admission,” the lawsuit alleges.

One child, Stephen W., was held in the hospital after he was cleared for discharge three times in 2014 and 2017, the lawsuit alleges. Last year, Stephen needed medication to help him sleep and cope with feelings of worthlessness and a fear that DCFS would not be able to find him a placement, the lawsuit alleges.

Another child, Alana M., was 13 in November 2014 when she was admitted to a psychiatric hospital with depression. She was still grieving the death of her adoptive mother, who had taken her in as a newborn, when she learned her adoptive grandmother had been diagnosed with late-stage cancer.

In an interview with ProPublica Illinois, Alana said she made progress in her first weeks at the psychiatric hospital and was ready for discharge by early January. She had an older sister in Indiana who wanted to take her in, but the DCFS approval process dragged on for months. As Alana waited, she said she grew more depressed. Her adoptive grandmother died while Alana was in the hospital. Alana said she tried to kill herself as a way to escape.

“I felt trapped,” she said. “I did everything I was supposed to do, but there was no point.”

An employee, who was later fired, forced her to perform sexual acts on him, according to the teenager and child welfare records. She was bullied by other girls at the hospital. By the time she left, she had been hospitalized for six months, 4 ½ of which were beyond medical necessity, and had not been able to go outside that entire time, the lawsuit alleges.

In a final blow, her doctors concluded that her prolonged stay had worsened her mental health to the point she could no longer move to her sister’s house but instead needed to be placed at a residential treatment center, the lawsuit alleges.

Alana said the lawsuit offers a glimmer of hope for children in an otherwise hopeless situation.

“It’s not going to give me back my time, but it’s justice for everybody else that’s going through it,” said Alana, who is now 17 and a high school senior. “Keeping us in the hospital is not going to make things any better. It’s going to make things worse.”

Skylar L. said her depression also worsened as she waited to be discharged from a psychiatric hospital in 2015. She celebrated her 16th birthday at the hospital and missed out on valuable schooling, the lawsuit alleges.

“I was always crying,” she said in an interview. “Who wants to be stuck in a hospital that long?”

She called her education at the hospital “a joke.” While group therapy was helpful at the beginning, she said, it quickly lost its benefit because “it was the same thing over and over again.” She said she constantly felt tired because of the medication she was given.

When Skylar was finally released, five months after she was admitted, she said DCFS placed her at a group home where some of the residents tried unsuccessfully to recruit her into a sex trafficking ring. She said she ran away for more than a month before returning to the group home and was eventually placed at a residential treatment center.

Several other plaintiffs named in the lawsuit are much younger. One boy was 5 when he was held beyond medical necessity at a hospital for two months in 2015. During that time, he couldn’t get special education services or meaningful therapy, the lawsuit alleges, and was only discharged following a court order.

The law firm Loevy & Loevy, which is best known for representing people who claim they were wrongly convicted, filed the lawsuit on behalf of Golbert and the former patients. Lawyer Russell Ainsworth said he see parallels between those who were forced to spend years wrongly imprisoned and the children locked in psychiatric hospitals.

The firm has represented ProPublica Illinois on open records and open meetings matters.

“For every innocent person that cried out for decades and nobody would listen,” he said, “these kids have been crying out for decades and no one has listened. They are stuck in a system that is balancing budgets on the backs of the most vulnerable children in Illinois. That’s wrong.”

Lawsuit targets Illinois’ child welfare agency over children languishing in psychiatric hospitals

Bio

Investigative reporter @ProPublicaIL, Chicago-based arm of @ProPublica. Formerly of @chicagotribune. Always a lover of chocolate.